The Musicarta Modes Workbook

The Minor Modes (2)

Transposing i-ëVII

Module Four of the Musicarta Modes workbook continues our look at the minor modes. Here are the riffs you’ll learn to play in this module.

Download up-to-date MIDI files for this page.

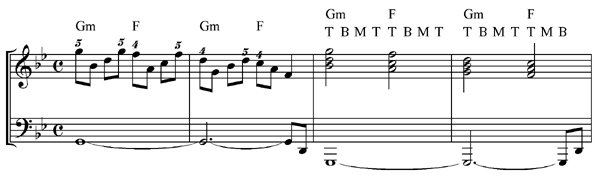

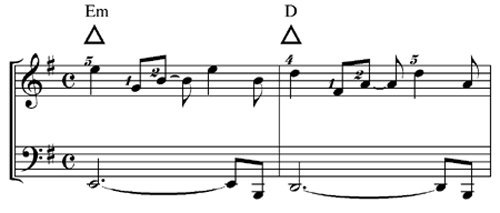

Riff One

Riff Two

Riff Three

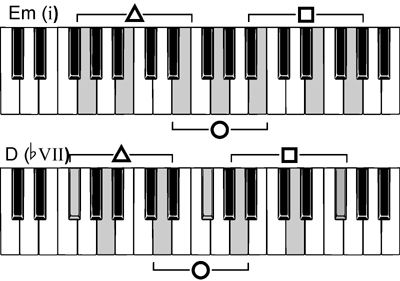

Finding i and ëVII anywhere

Module Four introduced the two i and ëVII (‘one and flat seven’) chord pairs you can find using the white piano keys only – A minor and G, and D minor and C.

But we can’t be limited to just the white piano keys. For lots of reasons, we want to be able find i–ëVII pairs in different places on the keyboard.

Transposing a simple pair of chords like this up or down on your keyboard is a core skill. Here are the logical steps of the process.

- i is a minor chord. We know because the RNS (Roman numeral system) chord symbol is lower case, not I (upper case). and lower case is reserved for minor chords. Because it’s ‘Number One’, it’s the naming chord of the mode or key: i in A Aeolian minor is the chord A minor; and so on.

- ëVII is a major chord. We know because the Roman numerals are upper case – not lower case, which would be vii and indicate a minor chord. We number chord according to the major scale, and the seventh degree of the major scale is a semi-tone below the tonic/home note. The flat sign in front of the VII (we have to use the letter b on web sites) asks for a note one semi-tone lower than that, i.e., a whole tone below i.

- So: i and ëVII are built on roots a whole tone apart. i is the higher of the two and is a minor chord; ëVII is lower and is a major chord

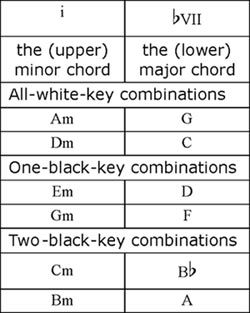

Here is a table of sample i / ëVII pairs. Ideally, you should be able to work out these pairs in your head.

Broken chord patterns and BMT analysis

In modern popular keyboard styles, the right hand mostly plays three-note chord, and you very often break these chords up and play the three chord tones one after the other in a nice rhythmic pattern. That way, you get more ‘mileage’ out of the chords you’ve learnt – and fill more bars with great music

‘BMT analysis’ is Musicarta’s broken chord shorthand. Thinking in terms of bottom, middle and top (BMT) chord tones is a powerful technique. After a while, broken chord patterns become semi-automatic; you set your hands to play a BMT pattern and ‘let your fingers do the talking’.

Broken chord patterns also offer more music for less thinking. Instead of thinking about three or four (or more0 notes, you only have to “think” the the pattern. Also, you can transpose a pattern more easily – all you need to do is get your hand over the new chord and press the ‘play pattern’ button in your head..

The i–ëVII broken chord riffs – Number 1

Let’s explore broken chord patterns in the G minor and F i–ëVII position.

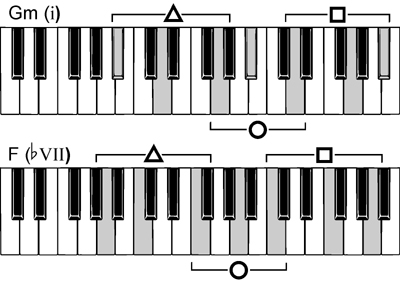

Here are the chords you need in a keyboard diagram.

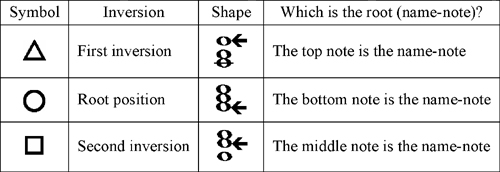

The chord tones are shaded and bracketed according to their inversions. Note that the inversion brackets only show you the shape of the chord, not where the chord you want actually is. Refer to the key again:

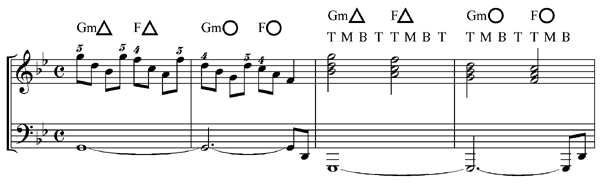

Here is the actual music you are going to play.

The first two bars of the music show the actual notes as you hear them in the audio clip. The next two bars – which sound exactly the same – show the chords you are playing, and how they are broken up into top, middle and bottom notes. You play top, middle, bottom, top (T, M, B, T) for each chord except the last F chord, which only uses top, middle, bottom (T, M, B).

‘Read’ the first two bars of music against the T,M,B,T pattern to see how the shorthand matches up.

Now listen to the next audio clip. A slight change to the bottom, middle, top order has been made. See if you can hear it and identify it (write it down in BMT shorthand) before looking at the music.

The inside two notes in each broken chord have swapped places. The pattern now runs T, B, M, T instead of T, M, B, T – except for the last F chord, where T, B, M would not work (try it!). Play the pattern yourself.

Finally, here is an alternating pattern – one of each variety in turn.

It’s a very small variation, but it stops the riff sounding mechanical.

To finish, the riff goes all the way from the top to the bottom. These are the chords and a possible BMT pattern – to match the last (‘alternating’) variation above.

Play the simpler T, M, B, T or T, B, M, T variations if you prefer. The audio plays the pattern that’s printed. Repeat the whole riff, then repeat the last two chords as a outro/fade.

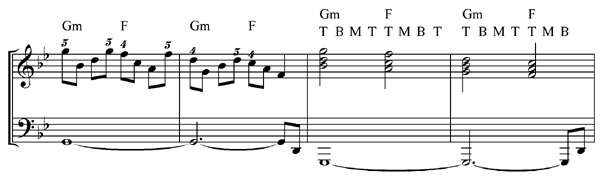

The i-ëVII broken chord riffs – Number 2

The more i–ëVII pairs you learn, the better you will grasp the pattern behind the music.

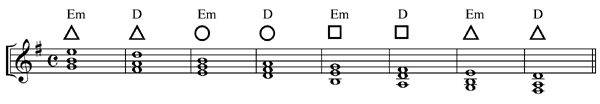

The next riff is a syncopated i–ëVII broken chord pattern in E minor (i) and D (ëVII).

Here is the audio clip:

You can hear that the right hand doesn’t play notes every beat – there are gaps and notes played off the beat. The rhythm is ‘syncopated’.

Here are the chords you need in a keyboard diagram:

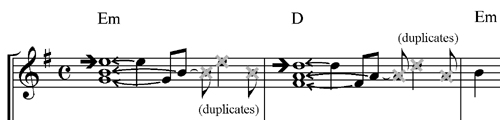

The first two bars of the riff written out look like this.

Whenever you see music like this that you

think might be a broken chord pattern, you should try to ‘bunch it back up’

(un-break it), so you can see what inversion is – like this:

You see that both chords are first inversions, with the root (name-note) at the top. This is a much more creative way of reading music.

Then you look at the bottom, middle, top order (‘BMT analysis’):

Play that pattern. Get your fingers over the notes and look at them as you play top, bottom, middle, top, middle - in any rhythm. Do the same with the D chord.

Next, try to get the rhythm. If you’re reading the music, you then see that there are tied notes and notes played off the beat, so you count the music out (in quavers), to see what beats the notes come on:

If you’re working mainly by ear, you count one to eight quickly to yourself as you listen to the audio – so that each note gets a number of its own – and try and work out which of the eight beats <b> don’t </b> have a note on them.

Counting one to eight evenly, you play the bottom, middle and top chord tones in the pattern you’ve identified. Practise repeating the first two chords first (E minor and D), then with the whole chord sequence.

This is the riff in the audio clip. The left hand (bass) notes are the roots, with a note B on quaver count eight.

Of course, you have the option of copying the structure of the first riff in this module – play the first four chords twice, then run all the way from top to bottom, repeating the last two chords for a ‘vamp’ (holding pattern), then repeating the whole thing.

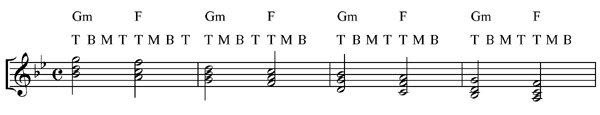

The i/ëVII broken chord riffs – Number 3

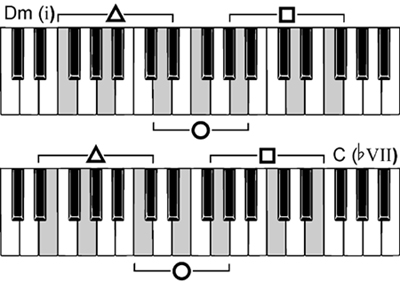

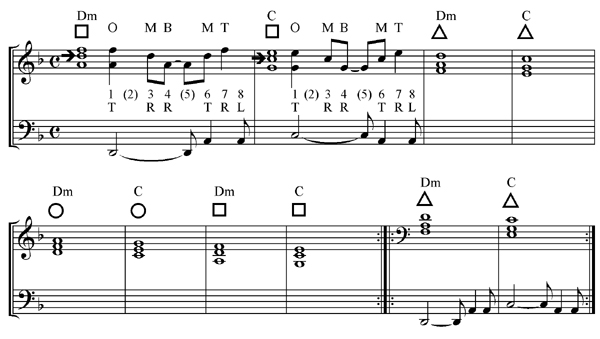

This riff is very similar to the last one, but we’re going to learn it in the D minor/C i–ëVII pair of chords which you already know. Here are the inversions in a table

Here’s the audio performance:

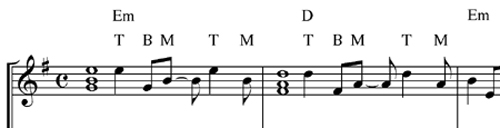

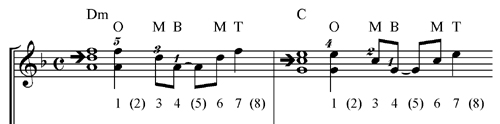

The first two bars of the riff that you hear, written out, look like this.

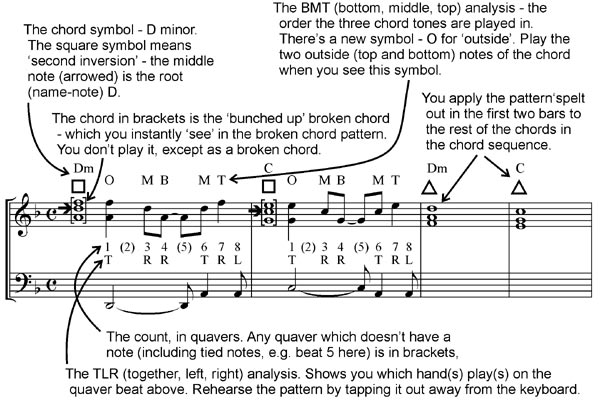

As before, you bunch the broken chord back up in your mind’s eye (or ear!) so that you can identify the inversion and the BMT pattern:

As before, you bunch the broken chord back up in your mind’s eye (or ear!) so that you can identify the inversion and the BMT pattern:

It’s a second inversion, represented by the square – the top two notes are closer to each other. (The other patterns so far have started with first inversions.) The name-note D is the middle note. Put the third finger on D and the other notes (thumb and fifth finger) should find themselves.

There’s a new symbol in this BMT pattern – 'O', for 'outside'. You play the outside notes of the chord – top and bottom – when you see 'O' in the BMT analysis.

But the right hand has a tricky rhythm. Count the audio riff out in quavers, one to eight. What counts do the notes come on?

Practice the rhythm on the right hand chords – copy the audio or skip down to the whole-riff chord sequence. Add a single-note (root) bass if you wish.

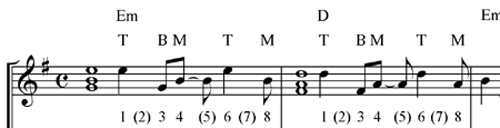

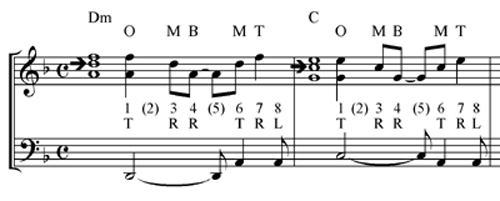

But we have to incorporate the bass line as well. Counting the bass, we find it comes on counts 1, 6 and 8, so the TLR (together, right, left) analysis is this (shown in between the staves).

It’s always worth tapping out a complicated rhythm like this away from the keyboard (i.e. without notes involved) until you’re quite comfortable with it before adding music to the mix.

Here’s the beat map audio. Count yourself in and tap along, then tap to the music MS.

The final diagram in this module shows all these things together. It’s a picture of what good pop/rock keyboard players do when they make up catchy riffs like the one in the audio clip.

There’s a lot of information here – don’t be scared off! It’s to read, not to play. Every bit of information here relates to a skill that’s worth having, so read through the text blocks one at a time, slowly.

Now, apply the pattern spelt out in these bars, as played in the audio clip, to the full chord sequence given here. The analysis has been left in in the first two bars, as a reminder. The bass notes are roots, with A as the in-between note.

As always with the Musicarta riffs, it’s fine if you just end up playing something similar or simpler. The point is to get a riff going and play it until your muscles remember it.

|

OUT NOW! |

THE MUSICARTA BEAT & RHYTHM WORKBOOK At last! An effective approach to keyboard rhythm & syncopation skills. Learn more! |

ONLY $24.95! |

MODES |

The MusicartaA methodical approach to keyboard syncopation for

|

PUBLICATIONS

exciting keyboard

creativity courses

CHORDS 101

WORKBOOK

~HANON~

video course

Musicarta

Patreon

PENTATONICS

WORKBOOK

video course

Creative Keyboard

video course

BEAT AND RHYTHM

WORKBOOK

- Volume 1 -

12-BAR PIANO

STYLES WORKBOOK

MUSICARTA MODES

WORKBOOK

PIANO STYLE

CANON PROJECT

video course

VARIATIONS

video course

- Piano Solo -

video course

- Piano Solo -

YouTube playlists

THE LOGO

THE LOGO